KDE Plasma and GNOME are the two most popular Linux desktop environments (DEs) that define user experience on the vast majority of Linux systems. While they share the goal of providing a graphical interface, their architectural decisions, design philosophies, and target demographics differ significantly.

This article will show the differences between KDE vs. GNOME to help you select the appropriate environment.

KDE vs. GNOME: Overview

The main differences between KDE and GNOME lie in their software frameworks and user interaction models:

- KDE follows a traditional desktop metaphor, giving users direct control over panels, widgets, and system configurations.

- GNOME centers on a minimalist workflow that removes desktop icons and taskbars in favor of a full-screen Activities Overview.

This difference influences everything from memory usage and dependency chains to the default application suites provided by each environment. The following table provides a high-level technical breakdown of both environments:

| Feature | KDE Plasma | GNOME |

|---|---|---|

| Design | Maximum configurability, traditional desktop metaphor. | Distraction-free minimalism, distinct Activities workflow. |

| Default look | Taskbar (Panel) at the bottom, application launcher, and system tray. Windows-like. | Top bar with clock/status, no visible taskbar or desktop icons by default. Mobile-like. |

| Default shell | Plasma Shell | GNOME Shell |

| Wayland support | Supports fractional scaling, tearing, and color management. | Stable but lacks some advanced protocols (e.g., server-side decorations). |

| File manager | Dolphin (Feature-dense, dual-pane, highly configurable). | Files/Nautilus (Simple, search-centric, limited options), |

| HDR support | Functional for gaming and video. | Experimental, limited availability. |

| Resource consumption | Moderate to Low (about 600MB–900MB idle RAM). | Moderate to High (about 900MB–1.3GB idle RAM). |

| Toolkit | Qt 6 | GTK 4/Libadwaita |

| Customization | Native, granular control over every element (panels, window rules, themes). | Limited native options. Relies on GNOME Tweaks. |

| Configurability | Complex settings menus with search. | Restricted. Promotes the default settings as best. |

| Extension system | Plasma Widgets (Plasmoids) with stable API. | GNOME Extensions; often break between major updates. |

| Accessibility | Functional but fragmented. Relies on Orca. | Tightly integrated. GNOME is the industry standard for visually impaired users. |

| Touch support | Tablet Mode adapts UI elements and has good gesture support. | Native, mobile-first design, with superior gesture integration. |

| Use cases | Power users, Windows migrants, gamers, tinkerers. | Developers, enterprise users, and minimalism enthusiasts. |

KDE vs. GNOME: In-Depth Comparison

KDE Plasma and GNOME use very different strategies for Linux desktop architecture and user interaction. While KDE is adaptable and centered on user agency, GNOME uses intentional design constraints to provide a standardized, distraction-free workflow.

The following sections go deeper into each comparison point.

Design Philosophy

KDE Plasma operates on the principle that the software should adapt to the user. It presents a familiar interface with a bottom panel featuring a menu on the left and a tray on the right.

Users can move and delete panels, create docks, or mimic macOS and Unity layouts natively. The design philosophy assumes the user knows best how to optimize their workflow.

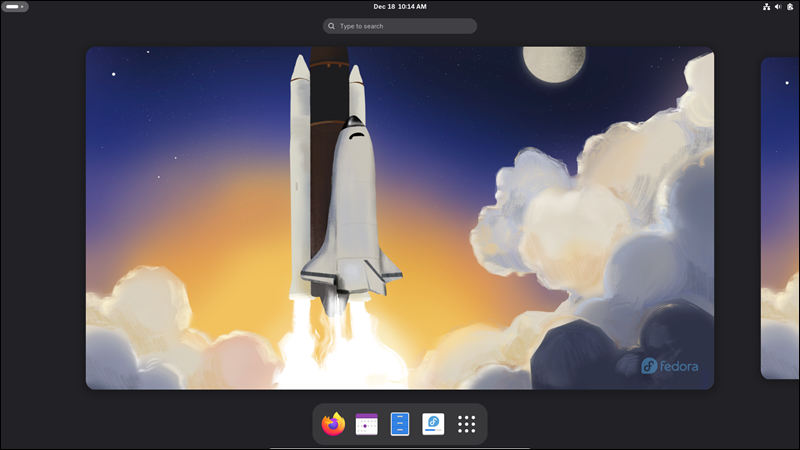

GNOME enforces a specific workflow designed to minimize distraction. It removes the desktop concept entirely and shows only a top bar with basic functions.

GNOME is based on the philosophy that constraints improve efficiency. By removing configuration options, GNOME ensures a consistent, predictable experience that allows users to focus on content rather than window management.

Default Look and Shell

Plasma Shell renders the visual interface in KDE. It uses widgets, i.e., Plasmoids, to build the desktop. The default panel contains a task manager, system tray, and digital clock. It supports traditional window management concepts, such as minimize, maximize, and a visible dock of open applications.

In GNOME Shell, the top bar displays only the Activities button, the clock, and system indicators. There is no always-visible taskbar. Users press the Super (Windows) key to enter the Activities Overview.

This action exposes open windows, virtual desktops, and the application grid. This approach forces a context switch when the user interrupts their work to manage windows and apps.

Wayland Support

As of late 2025, both environments function as full Wayland compositors.

KDE's compositor, KWin, supports fractional scaling (scaling UI at 125% or 150% without blur), tearing updates (crucial for low-latency gaming), and content recovery after a crash. KDE has announced plans to drop X11 support in future Plasma 6.x releases, demonstrating total commitment to Wayland.

GNOME's Mutter compositor was an early Wayland adopter and offers exceptional stability. However, it has been slower to adopt features that conflict with its design decisions, such as server-side window decorations (SSDs). GNOME forces client-side decorations (CSD), meaning applications must draw their own title bars. This leads to visual inconsistency when running non-GTK applications.

File Manager

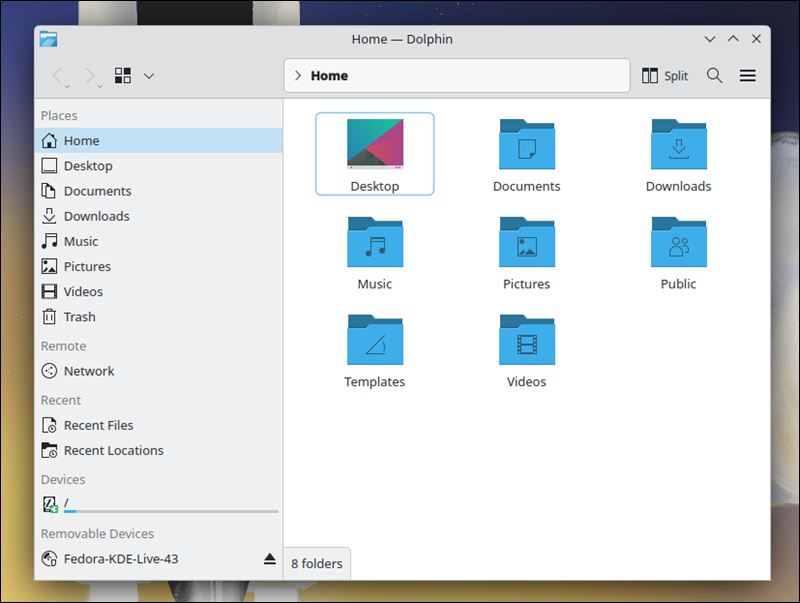

Dolphin (KDE) is often considered the most powerful file manager in the Linux ecosystem. It supports split views, integrated terminal panels, extensive plugin support, and configurability. Users can customize toolbar buttons, service menus, and view modes. It handles network protocols (SMB, SFTP) transparently.

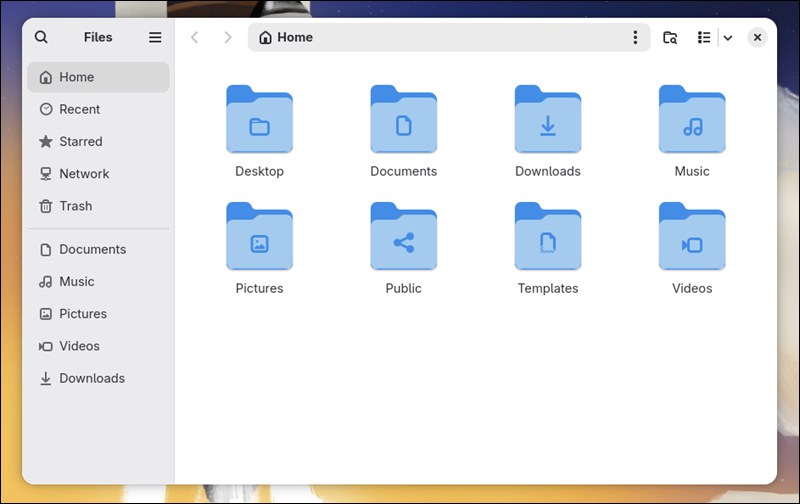

GNOME Files (formerly Nautilus) follows the "less is more" strategy. It presents a clean interface with a sidebar and a main view. It lacks the granular toolbar customization of Dolphin but integrates seamlessly with Google Drive and Nextcloud accounts via GNOME Online Accounts.

HDR Support

Collaborating with Valve (for the Steam Deck) and other stakeholders, KDE developers have implemented robust High Dynamic Range (HDR) support in KWin. Users can enable HDR on compatible monitors to ensure proper brightness mapping in games and movies.

GNOME's HDR support remains largely experimental. While the foundation exists in the display stack, the user-facing implementation lags behind KDE. Users specifically seeking HDR for media consumption or gaming will find that KDE is currently the only viable option.

Resource Consumption

Traditional assumptions that KDE is "bloated" and GNOME is "light" have been inverted. KDE Plasma 6 runs efficiently, often idling below 800MB of RAM on a cold boot. KWin disables compositing effects for full-screen applications to regain performance.

GNOME generally consumes more memory, often starting above 1GB. This stems partly from its JavaScript shell and background indexing services (Tracker). However, modern multi-core CPUs render the CPU overhead negligible in both environments. The difference mostly matters for hardware with 8GB of RAM or less.

Toolkit

KDE relies on the Qt 6 toolkit. Qt allows for complex, cross-platform applications with a native look and feel. It separates logic from the GUI, supporting Plasma's modular nature.

GNOME uses GTK 4 and the Libadwaita library. Libadwaita enforces strict adherence to GNOME's Human Interface Guidelines (HIG). While this guarantees that core GNOME apps look identical and polished, it makes them look out of place on other desktops. Libadwaita also hardcodes certain theming elements, making it difficult for users to apply system-wide themes to GNOME apps.

Customization and Configurability

KDE allows Global Themes that change the look of the shell, window decorations, icons, cursors, and application styles simultaneously. Users can download these from the system settings. Every behavior, from window focus rules to title bar button placement, is adjustable.

GNOME resists theming. The developers view themes as a compatibility nightmare that breaks application styling. Customization relies on GNOME Tweaks (a separate utility) and the dconf editor. Changing the shell theme requires installing a user shell extension.

Extension System

KDE Widgets are an important part of the KDE Plasma experience. The API is stable, and widgets generally persist across minor version updates.

GNOME Extensions are powerful JavaScript patches that modify the shell code at runtime. They can fundamentally change how the desktop works (e.g., adding a dock, enabling a system tray). However, because they patch internal code, they frequently break when GNOME updates. An extension works for GNOME 46 but may fail on GNOME 47, forcing users to wait for the developer to update it.

Accessibility

The Orca screen reader integrates tightly with GTK in GNOME, providing a reliable experience for visually impaired users. High-contrast modes and font scaling work consistently across the core system.

KDE has made progress, but the complexity of Qt and the sheer number of configuration options create edge cases where accessibility tools fail. The fragmented nature of the ecosystem means some apps work perfectly with screen readers while others do not.

Touch Support

GNOME was designed with touch in mind. The large UI elements, gesture-based workflow (three-finger swipe to switch workspaces), and on-screen keyboard function identically to a mobile OS. It is the superior choice for 2-in-1 convertibles.

KDE offers a Tablet Mode that automatically increases the padding between icons and taskbar buttons when a keyboard is detached. While functional, it still feels like a mouse-driven interface rather than a native touch interface.

Use Cases

KDE targets users who treat the computer as a personalized tool: developers who need specific window rules, gamers who need Variable Refresh Rate (VRR) and HDR, and power users who demand efficiency through configuration.

GNOME targets users who view the OS as a vehicle for applications: enterprise deployments that require stability and uniformity, laptop users who rely on trackpad gestures, and people who prefer a set-it-and-forget-it appliance.

KDE vs. GNOME: How to Choose

Use cases for KDE Plasma include:

- Gaming. The superior support for VRR, tearing updates, and HDR makes Plasma the default choice for Linux gamers.

- Windows migration. Organizations or individuals moving from Windows will find the paradigm shift minimal. The bottom panel and menu logic require little to no retraining.

- Multi-monitor setups. KWin offers extensive controls for placing windows on specific monitors and remembering positions, superior to GNOME's handling of complex monitor arrays.

- Content creation. The precision control over file management (Dolphin) and window placement benefits video editors and graphic designers who manage thousands of assets.

Use cases for GNOME include:

- Laptops and convertibles. The gesture-heavy workflow feels natural on a trackpad or touchscreen and is superior to KDE's mouse-centric design.

- Focus-critical work. Writers and academics often prefer GNOME because the interface is not distracting. There are no flashing taskbar entries or system tray icons.

- Enterprise workstations. System administrators prefer GNOME for its lack of options. A standardized interface reduces help-desk tickets related to broken user configurations.

- Accessibility needs. Users requiring screen readers or specific contrast settings will find a more reliable, cohesive experience in GNOME.

Conclusion

After reading this article, you are equipped to decide whether KDE Plasma or GNOME better aligns with your hardware and productivity style. The article provided a comprehensive technical comparison of the two environments, highlighting differences and providing use cases.

Next, learn how to install a desktop (GUI) on Ubuntu Server.