A parallel port is an older type of interface that allows computers to send multiple bits of data simultaneously to external devices.

What Is the Parallel Port?

A parallel port is a hardware interface on a computer that transmits multiple bits of data simultaneously over a set of parallel wires, typically eight data lines plus control and status lines. Traditionally implemented as a 25-pin D-sub connector (DB-25) on the back of desktop PCs, it was designed to connect peripherals such as printers, scanners, and external storage devices.

Unlike serial ports, which send data bit by bit over a single line, a parallel port can send an entire byte in one operation, which made it faster and more practical for early printing and data transfer needs. Communication over a parallel port is coordinated through specific signals that handle tasks like indicating when data is ready, when a device is busy, or when an error occurs, enabling relatively simple handshaking between the computer and the peripheral.

Over time, several standards were developed to extend its capabilities, including bidirectional transfer and higher throughput modes, but the basic concept remained the same: a wide, low-speed, short-distance connection optimized for direct attachment of nearby devices.

Although modern systems have mostly replaced parallel ports with USB and network interfaces, the parallel port is still relevant in legacy equipment, industrial control systems, and certain embedded or laboratory setups where its simplicity and direct hardware access are useful.

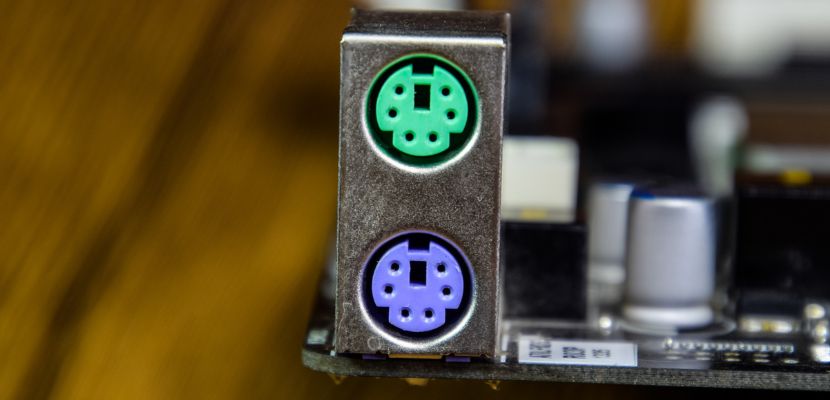

What Does a Parallel Port Look Like?

A parallel port typically appears as a wide, 25-pin connector (DB-25) on the back of older desktop computers. The port has a slightly trapezoidal metal shell with two small screw posts on either side for securing the cable. On the computer, the connector is usually female (with small holes), while the cable end is male (with visible pins).

In many PCs, the parallel port was often color-coded (commonly a light purple or pink surround) to distinguish it from serial, VGA, and other ports. On the printer side, the cable often ended in a larger, wider connector (often a 36-pin Centronics connector) that latched into the printer, giving the classic “thick printer cable” look associated with parallel ports.

How Does a Parallel Port Work?

A parallel port works by sending several bits of data at the same time over multiple wires, coordinated by control signals that keep the computer and device in sync. The process is simple but very structured, which is why it was so popular for printers and other early peripherals.

Here is a breakdown of how a parallel port works:

- The computer prepares a data byte. The CPU or a controller inside the PC takes 8 bits of data (one byte) that need to be sent to the device, such as a character to be printed. This byte is placed into the parallel port’s data register, which is directly connected to the 8 data lines on the port.

- The data lines are driven onto the cable. Once the byte is in the data register, the hardware sets the voltage levels on the 8 data pins to represent the ones and zeros of that byte. This effectively “puts” the data onto the cable so the connected device can read it.

- The computer signals that data is ready. The PC then toggles a control line (commonly called STROBE) to tell the peripheral that valid data is present on the data lines. This brief signal acts like a “ready” flag, letting the device know it should capture the data now.

- The peripheral reads and latches the data. The connected device monitors the control line and, when it detects the STROBE signal, it reads the voltages on the 8 data lines. It then latches this byte into its own internal buffer or memory, ensuring the data is safely stored even after the signals on the cable change.

- The device reports its status back. After reading the data, the peripheral updates its status lines (such as BUSY, ACK, or ERROR). BUSY might be asserted while the device processes the data, and ACK (acknowledge) is used to confirm that the byte was received. These status signals flow back to the PC over dedicated wires.

- The computer checks status and continues. The PC continuously monitors the status lines to see if the device is ready for more data. When it detects that the device is no longer busy and has acknowledged the previous byte, it knows it can safely send the next one.

- The process repeats for all data. This cycle of placing a byte on the data lines, strobing it, reading it, and acknowledging it repeats for every byte in the data stream. Together, these small, synchronized steps create a reliable, orderly transfer of data from the computer to the peripheral over the parallel port.

Parallel Port Uses

Parallel ports were originally designed for printers, but their simple, byte-wide interface made them useful for many other peripherals as well. Over time, they became a general-purpose way to connect external devices to PCs. Here are their main uses:

- Printers. The classic use of a parallel port was connecting a PC to a printer. The port sent characters and control commands to the printer quickly enough for typical print jobs, while status lines reported conditions like “busy,” “out of paper,” or “error.”

- Scanners and multifunction devices. Early flatbed scanners and some “all-in-one” printer–scanner–fax devices used parallel ports. They relied on the bidirectional modes of the port to both send scanned image data to the PC and receive control commands from scanning software.

- External storage devices. Before USB and fast external interfaces were common, some external hard drives, ZIP drives, and tape backup units used parallel ports. These devices often wrapped a higher-speed internal protocol (like IDE) inside a parallel port adapter, giving users portable storage without opening the PC.

- Hardware dongles and copy protection. Many older professional software packages used parallel-port dongles for licensing. A small device was plugged into the port, and the software checked for its presence before running. The dongle sometimes allowed other devices (like a printer) to daisy-chain through it.

- Industrial and laboratory equipment. Parallel ports were attractive in industrial control and lab environments because they offered direct, simple access to digital I/O lines. Engineers used them to control relays, read sensors, trigger instruments, or interface with custom measurement hardware.

- Prototyping, hobby projects, and custom electronics. Hobbyists and students often used parallel ports as a cheap, accessible way to experiment with digital electronics. By toggling individual bits on the data or control lines, they could drive LEDs, read switches, or communicate with microcontrollers without special interface hardware.

- Firmware programming and debugging (legacy). Some older development tools used the parallel port to program microcontrollers or EEPROMs and to interface with debug adapters. The direct bit-level control made it convenient for low-level programming and testing before dedicated USB programmers became standard.

When to Avoid Parallel Ports?

Parallel ports are useful in some legacy and niche setups, but they are usually a poor choice for new designs or modern environments. In most cases, other interfaces are faster, more reliable, and easier to support. Here is when to avoid parallel ports:

- High-speed data transfer needs. Avoid parallel ports when you need to move large amounts of data quickly (e.g., backups, media streaming, high-resolution imaging). Interfaces like USB, SATA, PCIe, or Ethernet offer far higher throughput and better performance.

- Modern consumer devices and laptops. Most new PCs, especially laptops, no longer include parallel ports. If you’re designing hardware or choosing peripherals for modern systems, relying on a port that isn’t physically present forces you into adapters and workarounds.

- Long cable runs or noisy environments. Parallel ports are designed for short, local connections. Over longer cables or in electrically noisy environments, signal integrity degrades easily. Digital buses or network-based protocols handle these conditions much better.

- Situations requiring hot-plugging and easy setup. Parallel devices usually expect the PC to be powered down when connecting or disconnecting, and drivers can be finicky. USB and network devices are much easier to plug in, detect, and configure on the fly.

- Environments with strict security and maintenance requirements. Because parallel ports expose low-level hardware signals, they can be harder to secure, monitor, and standardize than network or USB connections. In managed IT environments, using supported, modern interfaces simplifies security policies and maintenance.

- New designs and long-term support projects. If you are building a new product or system intended to last many years, basing it on a largely obsolete interface increases risk. Replacement parts, drivers, and technical support for parallel-port hardware will only become harder to find over time.

The Advantages and Disadvantages of Parallel Ports

Parallel ports played a key role in early PC connectivity, offering a straightforward way to attach local peripherals. However, their design also introduced limitations that became more apparent as data demands and device capabilities evolved. Understanding both the advantages and disadvantages of parallel ports helps explain why they were widely adopted in the past and why newer technologies have largely replaced them today.

Parallel Port Advantages

Parallel ports gained popularity because they offered a simple, practical way to connect early peripherals to PCs. Their design matched the needs of the time; namely, short-distance, low- to moderate-speed data transfer with minimal hardware complexity. The main advantages include:

- Simple, direct hardware interface. Parallel ports expose individual data, control, and status lines, making them easy to understand and work with at the electrical level. This direct access was ideal for early printers, custom electronics, and educational projects.

- Byte-wide data transfer. Unlike serial ports that send data one bit at a time, parallel ports transmit an entire byte simultaneously. For early PCs and printers, this provided noticeably faster data transfer than comparable serial interfaces of the era.

- Low cost and widely available (historically). For many years, almost every desktop PC shipped with at least one parallel port. This ubiquity meant that peripherals could be designed around a standard, low-cost interface without requiring special add-on cards.

- Basic handshaking built in. The presence of control and status lines (such as STROBE, BUSY, and ACK) enables simple, hardware-level handshaking between the computer and the device. This made reliable communication possible without complex protocols.

- Useful for prototyping and custom control. Engineers, hobbyists, and lab users could use the port as a general-purpose I/O interface to control relays, LEDs, sensors, and instruments. Being able to toggle and read individual bits directly from software made it a convenient tool for experimentation.

- Legacy compatibility. In environments that still rely on older equipment, such as industrial machines, lab instruments, or legacy printers, parallel ports remain an advantage because they provide native, compatible connectivity without needing protocol conversion.

Parallel Port Disadvantages

Parallel ports solved many connectivity problems in early PCs, but their design now shows clear limitations compared to modern interfaces. These drawbacks explain why parallel ports have largely disappeared from new hardware:

- Limited speed and scalability. Parallel ports were never designed for high data rates. As file sizes and device capabilities grew, their modest throughput quickly became a bottleneck, especially for tasks like large print jobs or external backups.

- Short cable length and signal issues. Because multiple lines switch simultaneously, parallel connections are sensitive to electrical noise and signal skew. Cable lengths are typically limited to a few meters and longer runs can cause errors or unreliable communication.

- Bulky connectors and cables. The DB-25 and Centronics connectors are large and cumbersome compared to modern ports. Thick, stiff parallel cables take up space, are harder to route, and are less convenient than compact USB or network cables.

- Unidirectional or limited bidirectional modes (legacy). Early parallel ports mainly supported one-way communication from PC to device. Although later standards added bidirectional modes, these were not always consistently implemented, limiting flexibility and compatibility.

- Poor support in modern systems. Most current desktops and almost all laptops ship without parallel ports. Using parallel devices now often requires USB adapters or expansion cards, adding complexity, potential driver issues, and extra points of failure.

- Higher CPU overhead and software complexity. Traditional parallel port access often relied on direct, low-level I/O operations from software. This could increase CPU overhead and require system-specific code, making drivers and applications more complex to maintain.

- Obsolescence and maintenance challenges. As the ecosystem has shifted to USB and network-based interfaces, replacement parts, updated drivers, and technical support for parallel hardware have become harder to find. This makes long-term maintenance of parallel-based systems increasingly difficult.

Parallel Port FAQ

Here are the answers to the most commonly asked questions about parallel ports.

What Is the Difference Between a Parallel Port and a Serial Port?

Let’s examine the differences between a parallel port and a serial port:

| Aspect | Parallel port | Serial port |

| Data transfer method | Sends multiple bits (typically 8) in parallel over many wires. | Sends bits one at a time over one or a few wires. |

| Typical connector | DB-25 on PC side, Centronics on printer side. | DE-9 or DB-25 (RS-232), later USB, etc. |

| Number of signal lines | Many lines (data, control, status). | Few lines (TX, RX, plus optional control lines). |

| Speed (historical context) | Faster than early serial ports for short distances. | Slower in early RS-232, later serial standards (USB, etc.) surpass parallel. |

| Cable length | Short distances (a few meters) due to noise and signal skew. | Generally supports longer runs more reliably. |

| Directionality | Originally one-way (PC to device), later bidirectional modes. | Typically full-duplex (send and receive simultaneously). |

| Cable/connector size | Bulky connectors and thick cables. | Smaller, lighter connectors and cables. |

| Complexity of wiring | More complex, many individual wires to manage. | Simpler wiring with fewer conductors. |

| Typical legacy uses | Printers, scanners, external drives, hardware dongles. | Modems, serial terminals, industrial equipment. |

| Prevalence in modern systems | Rare on new PCs; mostly legacy/industrial use. | Traditional RS-232 is rarer, but modern serial variants (USB, UART on boards) remain common in many devices and embedded systems. |

Can I Connect Multiple Devices on a Parallel Port?

In general, a standard parallel port is designed to communicate with one device at a time, not multiple independent devices like USB hubs allow. Some older printers and hardware dongles offered a pass-through connector so you could “daisy-chain” another parallel device, but the computer still treated the chain as a single logical connection, and compatibility could be unreliable.

There is no built-in addressing or hub mechanism in the parallel port standard, so for practical and reliable multi-device setups, modern interfaces such as USB or network connections are a much better choice.

Can a Parallel Port Transfer Data Between Two Computers?

Yes, a parallel port can transfer data between two computers, but only with the right cable and software. Historically, special “LapLink” or “parallel null” cables were used to connect the parallel ports of two PCs, and file-transfer programs handled the communication over the port’s data, control, and status lines. This setup allowed faster transfers than early serial links but required compatible software on both sides and careful configuration.

Today, this method is considered obsolete. USB transfer cables, external drives, or network-based file sharing are far easier, faster, and more reliable.

How Fast Does a Parallel Port Transfer Data?

Parallel port transfer speed depends on the specific mode and hardware, but it is slow by modern standards. Classic printer-style (Centronics) parallel ports typically reach around 50–150 KB/s in real-world use. Later enhanced modes, such as EPP (Enhanced Parallel Port) and ECP (Extended Capabilities Port), can push throughput into the range of roughly 500 KB/s to about 1–2 MB/s under ideal conditions.

Actual performance is often lower due to cable quality, driver efficiency, and how efficiently the software uses the port, which is one reason why USB and network connections have completely replaced parallel ports for high-speed data transfer.

Are Parallel Ports Secure?

Parallel ports are not secure by design. They provide low-level, unencrypted access to data and control signals, so anyone with physical access to the port and cable can potentially tap or interfere with communication. There is no built-in authentication, encryption, or access control, and traditional operating systems often expose the port directly to low-level software.

In modern environments, the overall risk is usually low because parallel ports are rare and used mainly in isolated or legacy setups, but if they are connected to sensitive equipment, security should rely on physical protection, network isolation, and strict control over who can access the machines that still use these ports.